Body Structure, Characteristics & Anatomy

Anatomy and Body Structure of the Porbeagle

A look at the external characteristics

The porbeagle shark, scientifically known as Lamna nasus, belongs to the family of mackerel sharks (Lamnidae) and is an elegant, highly specialized hunter of temperate to cool marine waters. With its streamlined, torpedo-shaped body, it is optimally designed for fast and enduring swimming.

The coloration of the porbeagle shark is distinctive: the upper side displays a metallic blue to dark grey hue, which sharply transitions to a bright white on the underside. This pronounced countershading serves as camouflage—seen from above, the shark blends in with the dark sea floor, while from below it merges with the bright surface of the water. In contrast to the tiger shark, the porbeagle shark has no stripes or spots.

Head and Snout

The head of the porbeagle shark is cone-shaped and tapers into a pointed snout. This conical form reduces water resistance and enables rapid turns during hunting. The nostrils are small and located ventrally (on the underside of the snout). As with all sharks, the nostrils are surrounded by ampullae of Lorenzini—electroreceptive sensory organs that can detect even weak electric fields emitted by prey animals.

Eyes and sensory organs

The eyes of the porbeagle shark are conspicuously large, round, and dark—an adaptation to life in temperate to cool waters, where light conditions are often limited. These large eyes allow good vision even in murky water or at dusk. Behind each eye there is a small spiracle, which in the porbeagle shark is barely functional and only rudimentary.

Gills and skin structure

The porbeagle shark has five long gill slits on each side of its body that enable oxygen uptake. These gills extend to the chest region but are shorter than those of other mackerel sharks like the great white shark. The skin is covered with placoid scales—tiny, tooth-like scales that give the skin a rough, sandpaper-like texture. These scales reduce flow resistance and provide protection against parasites.

Fin arrangement

The porbeagle shark has two dorsal fins. The first dorsal fin is large, triangular, and located roughly at the level of the rear edges of the pectoral fins. The second dorsal fin is much smaller and is positioned directly above the small anal fins. The pectoral fins are sickle-shaped and relatively short. The caudal fin is lunate (half-moon-shaped) and almost symmetrical—a typical feature of fast, pelagic sharks. A special anatomical characteristic is the presence of lateral keels on the caudal peduncle, which provide stability at high speeds.

Teeth and dentition

The dentition of the porbeagle shark is highly distinctive and differs significantly from other shark species. The teeth are slender, dagger-like, and smooth—without the serrated edges found in tiger sharks or great white sharks. They are ideal for gripping and holding onto smooth, fast-moving prey such as mackerel, herring, and squid.

In the upper jaw, the teeth stand upright, while in the lower jaw they are slightly inclined inward. At the base of each larger tooth, there are often smaller accessory cusps. As with all sharks, broken or worn teeth are continuously replaced by new ones from the back rows—an ongoing, lifelong replacement mechanism.

Sex Differences: Male vs. Female

Body Size and Weight

Porbeagle sharks show marked size differences between the sexes, with females generally growing larger and heavier than males. Adult females typically reach lengths of 2 to 2.5 meters, and in exceptional cases up to 3.6 meters. Males are usually somewhat smaller, reaching average lengths of about 1.8 to 2.4 meters.

There are also weight differences: females, due to their larger body mass, generally weigh more on average—large specimens can reach up to 230 kg, while males typically weigh between 60 and 135 kg.

Reproductive Organs and External Features

The most reliable external distinguishing feature between the sexes is the so-called claspers—paired, rod-shaped reproductive organs on the inner edges of the pelvic fins in males. These are clearly visible and serve to transfer sperm during mating. Females completely lack these structures.

Apart from the claspers and the difference in size, males and females are difficult to distinguish externally. Both sexes display the typical metallic-blue dorsal side and white underside, as well as identical fin shapes and tooth structures.

Maturation and Growth

Sexual maturity in porbeagle sharks occurs at different times depending on sex. Males become sexually mature earlier than females—usually when they reach a body length of 1.5 to 1.9 meters, corresponding to an age of about 4 to 8 years.

Females, on the other hand, need more time to mature. They reach sexual maturity only at lengths of about 2 to 2.2 meters, which can correspond to an age of 8 to 13 years. This longer development time is related to their energetically demanding reproductive system: female porbeagle sharks are ovoviviparous, meaning they carry the eggs inside their bodies until the young hatch and are born alive. The gestation period lasts about 8 to 9 months, and a litter typically consists of 1 to 5 young, which are already 60 to 75 cm long at birth.

Distribution & Habitat

Global distribution

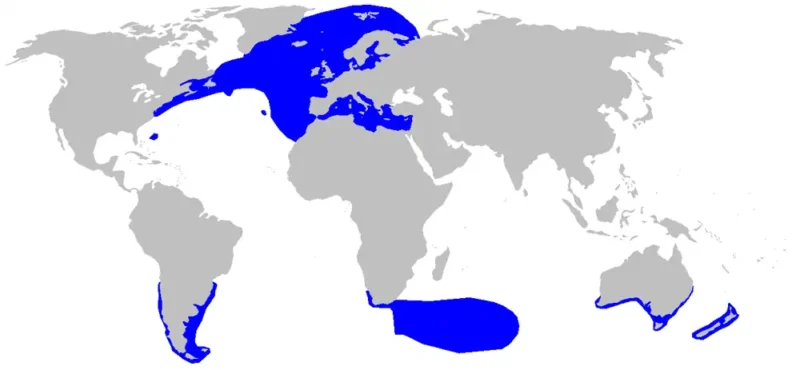

The porbeagle shark (Lamna nasus) is a typical inhabitant of temperate to cold marine regions and displays a characteristic transatlantic and transpacific distribution pattern. Unlike many other shark species, it prefers cooler water temperatures between about 5 and 18 °C and largely avoids tropical waters.

In the North Atlantic, the distribution area of the porbeagle shark extends from the east coast of North America—from Newfoundland to New Jersey—across Greenland and Iceland to the European coastal waters. Here, it is found from Norway and the British Isles through the North Sea to the Bay of Biscay and the western Mediterranean. Occasional sightings in the Mediterranean have been documented, but the porbeagle shark is much rarer there than in the open Atlantic.

In the South Atlantic, porbeagle sharks are found off the coasts of South Africa, Argentina, and southern Brazil, where they make use of cold ocean currents.

In the North Pacific, the species is widespread: from the coast of Japan and the Sea of Okhotsk across the Aleutians to the west coast of North America—from Alaska to southern California. In the South Pacific, porbeagle sharks are found off Australia, New Zealand, and Chile.

Habitats and depths

Porbeagle sharks inhabit both coastal and oceanic regions, showing remarkable flexibility in their depth range. They are mainly active between the surface and depths of 200 meters but have also been regularly recorded down to 700 meters. Occasionally, they dive as deep as 1,360 meters, for example when hunting deep-sea squids or during long-distance migrations.

They are particularly common in regions with high prey density — for example, in areas where schools of mackerel, herring, or squid occur. Coastal waters often serve as nursery grounds for juveniles, while adults tend to move farther offshore into the open sea.

Migration behaviour

The porbeagle is a highly migratory shark that covers great distances seasonally. These migrations are strongly influenced by temperature and food availability. Satellite tagging and catch data show that some individuals undertake transatlantic migrations between North America and Europe — sometimes covering distances of more than 3,000 kilometers.

In summer, porbeagle sharks often move to cooler northern waters, following the seasonal presence of prey fish such as herring or mackerel. In autumn and winter, many populations return to warmer, southern regions or retreat to deeper water layers where temperatures remain more stable. This pronounced north–south migration pattern makes them one of the most mobile shark species in temperate regions.

Juveniles tend to remain longer in coastal areas, while mature individuals prefer oceanic habitats and travel long distances across open water.

Typical Habitats

Porbeagle sharks are adapted to cooler, temperate waters and show a clear preference for certain marine regions. Unlike tropical species such as the tiger shark, they favor lower temperatures and can be found both in coastal and pelagic zones.

Coastal Waters

Porbeagle sharks are often found on continental shelf areas, where they hunt at depths ranging from 0 to about 200 meters. They prefer coastal regions rich in fish, especially areas with schools of mackerel, herring, and sardines. In these zones, they regularly patrol along rocky coasts, bays, and sandbanks.

Open Ocean

As a highly pelagic shark, the porbeagle can also be found far out in the open sea. It follows migrating schools of fish and can cover great distances. In these areas, it usually moves at depths between 50 and 250 meters, but can also reach depths of over 1,360 meters.

Temperature preference

A key feature of the porbeagle is its adaptation to cool water temperatures. It prefers waters between 5 and 15 °C and is therefore mainly found in the temperate regions of the North Atlantic and the southern Pacific. In summer, porbeagle sharks often follow cold currents northward, while in winter they retreat to warmer southern regions.

Differences Between Age Groups

Juvenile sharks spend their first years of life mostly in shallower, coastal waters, where they are better protected from larger predators and have abundant food. Adult porbeagle sharks are significantly more mobile and undertake extensive migrations between feeding and breeding grounds. They use both coastal zones and the open sea, displaying pronounced seasonal migratory behavior.

Lifestyle, diet & reproduction

General Lifestyle and Behavior

The porbeagle (Lamna nasus) is a highly active solitary shark that prefers the cooler waters of temperate regions. These animals only occasionally form groups when prey density is particularly high—such as during seasonal mackerel shoals or herring migrations. In such cases, several individuals hunt together, but without developing a fixed social structure.

Porbeagles are among the fastest and most enduring swimmers of all sharks. Their torpedo-shaped body, crescent-shaped tail fin, and lateral keels on the caudal peduncle allow for high speeds and agile maneuvers. They prefer to hunt in open water (pelagic) and actively pursue fast-moving prey over long distances.

A biological peculiarity of the porbeagle is its ability for regional endothermy. Using a counter-current heat exchange system (rete mirabile), it can maintain its body temperature—especially in the muscles, eyes, and brain—several degrees above the surrounding water. This allows it to remain agile and responsive even in cold waters.

Diet and hunting strategy

The porbeagle feeds mainly on medium-sized bony fish. Its preferred prey includes mackerel, herring, hake, horse mackerel, and sardines. Squid and other cephalopods also feature regularly in its diet. More rarely, the porbeagle preys on smaller sharks, rays, or other cartilaginous fish.

Hunting takes place mainly in open water and is aided by the porbeagle’s excellent vision and rapid swimming movements. Porbeagles use surprise attacks and short bursts of speed to break up schools of fish and isolate individual prey. Their slender, dagger-like teeth are perfectly adapted for gripping and holding onto smooth, fast-moving prey.

Reproduction

The porbeagle is ovoviviparous, meaning it gives birth to live young from eggs hatched inside the mother. The fertilized eggs develop in the womb, and the pups hatch before birth. The gestation period lasts about 8 to 9 months. Each litter produces between 1 and 5 pups, which already reach a length of 60 to 75 cm at birth.

Females reach sexual maturity late—usually between 8 and 13 years of age, at a body length of about 2 to 2.2 meters. Males mature earlier, between 4 and 8 years, at lengths of 1.5 to 1.9 meters. The relatively small litter size and long reproductive intervals make the species particularly vulnerable to overfishing.

Characteristics and threats

One of the most remarkable traits of the porbeagle is its endothermy—the ability to generate and retain body heat. This gives it a clear advantage over cold-blooded fish in colder waters and allows for a wider geographical distribution.

The porbeagle is highly endangered due to its slow reproductive rate and long developmental period. Intensive fishing—both as bycatch and targeted—has drastically reduced populations worldwide. In many regions, stocks have already collapsed or are in severe decline. Shorter reproductive intervals caused by fishing pressure further worsen the problem, as populations are unable to recover sufficiently.

@gioscuba A clip I feel the need to put out there every so often as it was my most memorable underwater encounter I have ever had in the UK. This was off shore from Penzance, Cornwall while looking for blue shark we had a quick encounter with this stunning porbeagle! 🦈 #cornwall #penzance #diving #ukdiving #uksnorkelling #ocean #porbeagle #uksharks #sharkdiving #sharkencounter #cornwallshark ♬ voices - Øneheart

Reproduction and Life Cycle

Porbeagles are ovoviviparous, meaning the young first develop from eggs inside the mother’s womb, hatch there, and are then born alive. During gestation, the embryos initially feed on the yolk and later also through oophagy, meaning they consume unfertilized eggs that the female continues to produce.

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Reproduction Cycle | approximately every 1 to 2 years per female |

| Gestation period | approximately 8 to 9 months |

| Litter Size | between 1 and 5 offspring, usually 3 to 4 |

| Size at Birth | around 60 to 75 cm |

| Sexual Maturity | Males about 1.5 to 1.9 m, females about 2.0 to 2.2 m in length |

| Estimated Lifespan | approximately 25 to 45 years |

Mating usually takes place in late summer or autumn. Males and females gather in specific areas, where mating is initiated through repeated circling and body contact. Males often bite the females’ pectoral fins to hold on during copulation.

Birth usually occurs in early summer in temperate coastal waters. Young porbeagles are born fully developed and are immediately independent. There is no maternal care after birth. The juveniles prefer to stay in shallower coastal areas, where they are better protected from larger predators and can find sufficient food.

Porbeagles grow relatively slowly and reach sexual maturity only after several years. Males mature earlier (at 4 to 8 years), while females take longer (8 to 13 years). This slow reproductive rate makes the species particularly vulnerable to overfishing.

Humans & Porbeagles Sharks

Natural shyness and encounters with humans

The porbeagle displays a natural shyness toward humans and only rarely approaches them. Encounters between divers or swimmers and porbeagles are extremely rare. To date, there are very few documented attacks on humans—the species is considered harmless. Even in direct encounters, the porbeagle behaves cautiously and generally avoids contact.

For divers, the porbeagle is an extremely fascinating but hard-to-observe animal. Due to its preference for cool, temperate waters and its shy nature, sightings are rare and considered a special experience.

Known sighting areas for porbeagles

There are some regions where porbeagles are sighted more regularly, which are of interest to dedicated divers:

• Wales (United Kingdom): Off the coast of Wales, especially around Pembrokeshire, porbeagles are repeatedly observed. The cool, nutrient-rich waters provide ideal conditions.

• Ireland: The Irish coastal waters are also known for occasional porbeagle sightings, especially in summer and autumn.

• South Africa: In the cooler waters off the South African coast, especially in the Atlantic, there are occasional encounters with porbeagles.

Despite these known areas, the porbeagle remains a rare and highly sought-after sight for divers.

Threat from fishing

The porbeagle has been heavily affected by commercial and recreational fishing for decades. Its meat is valued and processed into steaks, its fins are used in fin soup, and its liver oil is utilized in various industries. This diverse use has led to intensive hunting of the porbeagle, which continues to this day.

In addition to targeted fishing, porbeagles are often caught as bycatch in longline and gillnet fisheries. This unintended removal from the population contributes significantly to the species’ endangerment. Many animals die in the nets or on the hooks before they can be released.

The porbeagle is also a sought-after target in recreational fishing. Due to its strength and speed, it is considered a challenging catch. Despite increasing catch-and-release practices, many animals die from the stress of the fight or from hook injuries.

Population decline and conservation measures

Due to decades of overfishing, porbeagle populations have declined dramatically in many regions. Significant declines have been documented, especially in the North Atlantic, where the species was historically widespread.

In response to this development, numerous international conservation measures have been requested and partially implemented:

• The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) classifies the porbeagle as "Vulnerable."

• In various countries and regions, catch limits, minimum size requirements, or complete bans on porbeagle fishing apply.

• The European Union and other fishing nations are working on sustainable management plans to stabilize and preserve porbeagle populations in the long term.

• Scientific programs for population surveys and tagging of porbeagles provide important data for species conservation.

Despite these efforts, the future of the porbeagle remains uncertain. Its slow reproductive rate—females mature late and produce only a few offspring—makes population recovery particularly difficult.

Threats & Population Development

The porbeagle (Lamna nasus) is one of the most endangered shark species worldwide. Despite its once wide distribution in temperate to cool seas, the species has declined drastically or nearly disappeared in many regions due to massive overfishing. This article takes a detailed look at the current threat status and population trends of the porbeagle.

Global population trends: an alarming decline

Porbeagle populations have collapsed massively worldwide over the past decades. The situation is particularly dramatic in the North Atlantic, where the species was historically most common. In the North Sea and Baltic Sea, the porbeagle is now considered nearly extinct—sightings have become rare, and a reproducing population practically no longer exists.

Even in the Mediterranean, where porbeagles were once regularly encountered, the species is now extremely rare. Catch statistics show a decline of over 90% since the mid-20th century. In the northeastern Atlantic—off the coasts of Great Britain, Ireland, Norway, and Iceland—populations still exist but are also highly threatened and far below historical levels.

Smaller, but also declining, populations are found in the North Pacific (off Alaska, Canada, and Japan) as well as in the South Atlantic (off Argentina and South Africa). Studies there also show a continuous population decline, though not as dramatic as in the North Atlantic.

Main threats: Why is the porbeagle so endangered?

Targeted fishing

The porbeagle was the target of intensive commercial fishing for decades. Its meat is considered tasty and was marketed as food in many countries—especially in Scandinavia, Great Britain, and North America. Additionally, its fins were used for the Asian market and its liver oil for pharmaceutical and cosmetic purposes.

Targeted fishing using longlines, gillnets, and trawl nets led to massive catches. In the 1960s and 1970s, thousands of tons of porbeagles were caught annually in the North Atlantic—far more than the populations could sustain.

Bycatch

In addition to targeted fishing, bycatch also poses a significant problem. Porbeagles often get caught in nets set for other fish species such as cod, mackerel, or tuna. Since many fishing fleets are not required to accurately document bycatch, the actual number of porbeagles killed as bycatch is likely much higher than officially recorded.

Low reproduction rate

One of the main reasons for the porbeagle’s endangered status is its extremely slow reproductive biology. Females reach sexual maturity only at 8 to 13 years of age, while males mature between 4 and 8 years. Pregnancy lasts 8 to 9 months, and each litter produces only 1 to 5 pups.

This low reproduction rate means that porbeagle populations can recover only very slowly — even if fishing pressure decreases. Compared to many bony fish species that produce thousands of eggs per year, the porbeagle is biologically extremely vulnerable to overfishing.

Imbalance between fishing pressure and recovery potential

The main problem in protecting the porbeagle is the severe imbalance between the high fishing pressure and the species’ low recovery potential. Even after the introduction of catch limits or conservation measures, it can take decades for populations to recover significantly — provided that fishing pressure actually remains low.

In many regions, however, fishing was only stopped after the populations had already collapsed. By that time, the population size was so low that natural recovery has become extremely slow or even impossible.

Protection status and measures

IUCN classification

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies the porbeagle globally as “Endangered”. In some regions, particularly in the Northeast Atlantic and the Mediterranean, the species is listed as “Critically Endangered”. This classification highlights the urgent need for conservation measures.

CITES Appendix II

Since 2014, the porbeagle has been listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). This means that international trade in porbeagle products (meat, fins, oil) must be strictly regulated and monitored. Exporting countries must prove that the catch is sustainable and that the species is not further endangered.

Protection in the EU

In the waters of the European Union, the porbeagle has been strictly protected since 2010. A complete fishing ban applies to all EU member states. Bycatch must also be released immediately if the animal is still alive. These measures are an important step in protecting the severely depleted European populations.

Fishing bans and regulations

In addition to the EU, other countries and regional fisheries organizations have also implemented conservation measures:

– Norway and Iceland have drastically reduced or temporarily suspended catch quotas.

– Canada has introduced catch limits for the Atlantic coast.

– In New Zealand and Australia, strict regulations apply to bycatch.

Nevertheless, many regions still lack effective monitoring and enforcement mechanisms.

Successes and failures in conservation

Successes

In some regions, conservation measures are showing initial positive effects. Off the coasts of Ireland and the United Kingdom, porbeagle sightings have increased in recent years, which could indicate a slight recovery. Tracking studies have also provided valuable insights into migration routes and habitat use, which can be used for targeted conservation efforts.

Failures and challenges

Nevertheless, the overall situation remains critical. In many regions, populations are so severely depleted that recovery is uncertain. Illegal fishing, insufficient monitoring, and high bycatch in international waters remain key problems.

Moreover, there is a lack of comprehensive data on population sizes and trends in many parts of the species’ range, which makes planning and implementing effective conservation strategies difficult.

Conclusion: Urgent need for action

The porbeagle exemplifies the fate of many highly mobile, slow-reproducing marine predators. Without consistent international protection, effective monitoring, and an end to overfishing, the species will continue to decline or disappear entirely in large parts of its range.

Stronger efforts are urgently needed — both at the political level through international agreements and through scientific research and public education — to ensure the long-term survival of the porbeagle.

Population development in different regions

The global trend of the porbeagle population is alarming. Long-term surveys and regional studies show a dramatic decline that has been ongoing in many regions for decades.

Northeast Atlantic

In the Northeast Atlantic, where porbeagles were historically common, populations have collapsed dramatically. Data from European fisheries surveys show that catch rates have declined by over 80 percent since the 1960s. The stocks in the Northeast Atlantic are particularly affected, where commercial fishing and bycatch have severely depleted populations.

The average size of the caught animals has also decreased, indicating that particularly large, sexually mature individuals have disappeared from the populations. This has long-term consequences for the regenerative capacity of the populations.

Northwest Atlantic

In Canadian and U.S. waters, the situation is similarly critical. A continuous decline has been observed since the 1960s. Although commercial fishing for porbeagles has largely ceased in Canada, population recovery is extremely slow or has completely stagnated. Scientists estimate that stocks in the Northwest Atlantic have declined by 70 to 90 percent.

A particular problem is bycatch in longline fisheries. Many porbeagles die before they can reproduce, which greatly hinders population recovery.

South Atlantic and southern Pacific

Worrying trends are also observed in the temperate waters of the Southern Hemisphere. In Argentina, Chile, and New Zealand, porbeagle populations have declined sharply over recent decades. In these regions, the species is regularly caught as bycatch in industrial fisheries.

The situation is particularly dramatic in Argentine waters, where intensive bottom trawl fisheries have heavily impacted porbeagle populations. Estimates suggest a decline of at least 50 percent over the past 30 years.

Recovery prospects and future outlook

The recovery of porbeagle populations is extremely difficult due to their biological characteristics. Porbeagles grow slowly, reach sexual maturity late, and have a low reproductive rate (only 1 to 5 pups per litter). These factors make the species particularly vulnerable to overfishing.

Even with a complete fishing ban, population recovery would take decades. Scientists warn that without strict conservation measures and international cooperation, the global porbeagle population will continue to decline. The worldwide trend is downward, and there are currently no signs of a reversal.