Body Structure, Characteristics & Anatomy

The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is among the largest sharks and impresses with its robust, torpedo-shaped body and unique anatomical features. This article describes the most striking external and internal characteristics of this species and explains the physical differences between males and females.

Hardly any marine animal is as feared and at the same time as fascinating as the great white shark. But how is this apex predator of the oceans actually built? In the following, we take a closer look at the body structure and special anatomical features of the great white shark – from its distinctive teeth to the differences between males and females.

Size and body shape

The great white shark, with an average length of about 4 meters and a maximum of over 7 meters, ranks among the largest shark species. Adult females grow significantly larger than males; while males usually reach a maximum of around 5 meters, females can exceed 6 meters in length. Their weight is equally extraordinary: a large great white shark can weigh up to three tons.

The body shape of these sharks is compact and spindle-shaped (torpedo-like) with a blunt, conical snout. This streamlined build allows both endurance swimming and rapid bursts of speed during hunting. In fact, the muscular bodies of great white sharks are designed to generate sudden accelerations. Their eyes are positioned on the sides of the head, relatively small, and completely black (the pupil is not visible). Notably, great white sharks do not have a nictitating membrane; for protection, they roll their eyes backward during attacks.

As a cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes), the great white shark does not have a bony skeleton but instead a lightweight skeleton made of cartilage. This lighter, flexible skeletal structure, together with a large oil-filled liver, provides buoyancy, since it lacks a swim bladder like bony fish. Continuous movement is essential for breathing: like most large sharks, it must swim permanently through the water to pump water through its mouth and the five large gill slits in order to absorb oxygen.

Skin and coloration

The great white shark displays a dorsal coloration typical of predatory fish: the upper side ranges from light gray to brown, sometimes bluish or nearly black, often with a bronze sheen. In contrast, the underside is bright white, sharply separated from the darker flanks. This so-called countershading helps the shark remain less visible in the water: from above, its dark back blends with the deep water, while from below, the pale belly matches the light coming from the surface. A distinctive feature is a usually dark spot at the base of the pectoral fins (behind their origin) as well as black tips on the underside of the pectoral fins. The individual spotting and coloration pattern around the gill area is unique to each shark, allowing researchers to identify individual great whites.

The skin of the great white shark is exceptionally tough and resembles sandpaper. It is covered with millions of tiny placoid scales – small tooth-like structures known as dermal denticles. These skin teeth are directed backward, reducing drag and allowing the shark to swim more efficiently and silently. At the same time, the rough skin provides protection against injuries and parasite growth. When stroked from head to tail, the skin feels smooth, but in the opposite direction it can scrape the hand raw. The special structure of shark skin has even inspired engineers: high-tech applications such as specialized swimsuits or antiseptic surfaces mimic the ridged texture of shark skin.

Fins and locomotion

All fins of the great white shark are developed without fin spines. The first dorsal fin is large, triangular, and slightly sickle-shaped; it begins roughly at the rear end of the pectoral fins. A second, much smaller dorsal fin is located further back and starts just before the anal fin. The pectoral fins themselves are long and powerful, serving as rudders and lift surfaces. On the caudal peduncle (tail base), there is a prominent lateral keel that increases stability during fast swimming maneuvers. The tail fin is large, crescent-shaped, and nearly symmetrical – the lower lobe is almost as large as the upper one. This homocercal (symmetrical) tail shape, together with strong trunk musculature, provides powerful propulsion. Great white sharks swim primarily with strong tail beats (thunniform swimming pattern), moving the trunk only minimally sideways. They can accelerate explosively from a standstill and even leap completely out of the water when hunting prey such as seals. However, most of the time they move at a leisurely pace, cruising at around 3 km/h, though they can cover daily distances of 70–80 km.

The powerful trunk musculature of the great white shark is supported by a special thermoregulatory system. Unlike most fish, this shark is partially warm-blooded: specialized networks of fine blood vessels (the rete mirabile) act like a heat exchanger, retaining the heat generated by muscle activity inside the body. This allows vital organs such as the brain, eyes, and swimming muscles to be maintained at a higher temperature. As a result, the core body temperature of a great white shark is several degrees Celsius above the surrounding water – with studies reporting around a 10 °C difference. This adaptation increases performance, particularly when hunting in cooler waters, as muscles and senses function more efficiently in warmth.

Teeth and dentition

The dentition of the great white shark is one of its most striking features. The broad, arched mouth of large individuals measures almost one meter in diameter and contains several rows of teeth. In the foremost active row, the upper jaw carries about 23 to 28 triangular teeth, while the lower jaw has about 20 to 26. These teeth are broad, flat, and sharply serrated along the edges (saw-like) – perfect weapons for cutting prey apart. As in all sharks, worn or lost teeth are continuously replaced by reserve teeth from the back rows; over its lifetime, a great white shark can lose and renew several thousand teeth. This arrangement is known as a “revolving dentition.” In each row, the teeth form a continuous cutting edge, with the largest teeth positioned at the tip of the snout. When biting, the upper and lower jaws fit together perfectly: the pointed lower teeth grip the prey, while the large, serrated upper teeth tear out chunks of flesh. The bite force of a large great white shark is immense and can easily crush bones.

Interestingly, unlike tiger sharks for example, the great white shark does not have a nictitating membrane to protect its eyes. Therefore, during the final bite on its prey, it rolls its eyeballs backward to shield them from injury – giving it a “white eye” during the attack, which may be the origin of its German name.

Sense organs

As a highly developed predator, the great white shark is equipped with astonishing sensory abilities. Its sense of smell is legendary: sharks can detect the tiniest traces of blood in the water. Their hearing also perceives low-frequency vibrations and sounds over great distances. Along the sides of the body runs the so-called lateral line organ, a sensory canal that allows the shark to detect pressure waves and movements in the water.

The great white shark has special organs for detecting electric fields: in small jelly-filled pits around the snout, the ampullae of Lorenzini register the bioelectricity of other living beings – for example, the heartbeat of hidden prey. Its vision is also better than once assumed: although great whites have relatively small, uniformly black eyes, they can perceive contrasts and movements well, and even see colors. When hunting prey, they protect their eyes by rolling them backward – due to the lack of eyelids – as mentioned above. The interaction of these senses makes the great white shark an efficient hunter. It can detect prey from long distances, locate it with hearing and the lateral line, and pinpoint it in the final attack using sight and electroreception.

Differences between males and females

In great white sharks, there is a pronounced sexual dimorphism in body size: females clearly surpass males in both length and mass. While males average around 3.5 to 4 meters in length, females reach average lengths of 4.5 to 5 meters. The largest known individuals – such as the famous female “Deep Blue” – have even exceeded 6 meters. Females are also generally more robust in build and have a broader head, which may be related to their role in reproduction (carrying embryos).

A clear distinguishing feature between the sexes can be found on the underside of the body: males have a pair of visible reproductive organs on the pelvic fins, the so-called claspers. These are modified fins and, in sexually mature males, can reach up to 50 cm in length (about 10% of the body length). Females do not have claspers.

During mating, males often bite females on the fins or back to hold on. As a result, females frequently bear scars from these “love bites.” To better withstand such injuries, the skin of females is noticeably thicker than that of males – in some shark species up to three times thicker. Apart from size and the features mentioned, male and female great white sharks show little morphological difference. Both sexes have the same coloration and essentially identical body shape.

Distribution & Habitat

The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is a globally distributed predator found both in coastal areas and the open ocean. It prefers water temperatures between 12 and 24 degrees Celsius and stays where sufficient food is available. Its habitat extends from the coasts of the Atlantic through the Pacific to the Indian Ocean, as well as into the Mediterranean Sea.

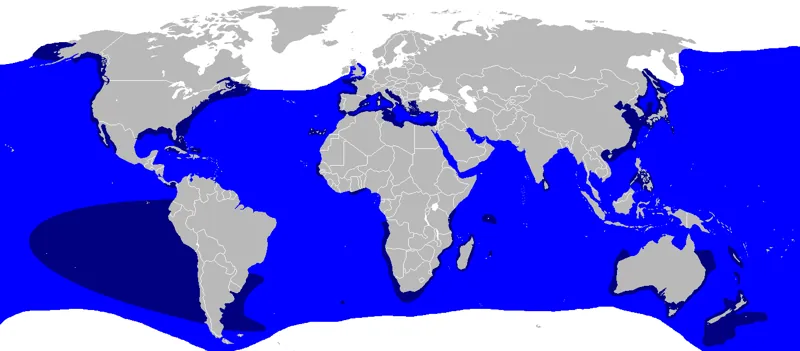

Global distribution

In the Atlantic, the distribution ranges from Canada and the United States through the Caribbean down to South America. In the eastern Atlantic, great white sharks have been recorded from Europe to the African coast and throughout the Mediterranean. In the Pacific, they inhabit the coasts of North America, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and South America. In the Indian Ocean, they occur off South Africa, the Seychelles, and in the Red Sea, among other places. Particularly well-known hotspots include South Africa, California, and South Australia, where the animals regularly gather near seal colonies.

Habitat coast and open sea

Great white sharks use a variety of habitats: coastal waters with rocky reefs or sandy beaches, as well as the vast open ocean. Juveniles stay mostly in shallower and warmer regions that provide them with protection. Adults, on the other hand, move between coastal hunting grounds and pelagic zones, where they search for food at depths of up to 1,300 meters. Their ability to maintain body temperature above that of the surrounding water allows them to survive in a wide range of temperatures.

Nursery areas

There are specific nurseries for juveniles. Off California and the U.S. East Coast, particularly between New Jersey and Massachusetts, young great white sharks have been repeatedly observed. The Mediterranean, especially the Adriatic Sea and the Sicilian Channel, is also considered an important nursery area. These regions provide abundant food and relatively safe conditions.

Migration routes of the great white shark

The great white shark is known for its long migrations. These can be seasonal along coasts or span great distances across the open ocean.

Seasonal coastal migrations

On the U.S. East Coast, great white sharks follow a fixed pattern: in summer they migrate north as far as Newfoundland, while in winter they move south to the Caribbean. Similar movements can be observed in South Africa and Australia, when the animals return to the seal colonies.

The White Shark Café

A unique phenomenon is the so-called White Shark Café, a region in the middle of the Pacific between California and Hawaii. Many sharks from the northeast Pacific spend the winter months there. They regularly dive to great depths and apparently take advantage of the rich food resources in the open ocean.

Transoceanic migrations

Some individuals cover enormous distances. A famous example is a female that swam almost 20,000 kilometers from South Africa to Australia and back. Such journeys show that populations in different oceans may be more closely connected than long assumed.

Lifestyle, diet & reproduction

As the apex predator of the oceans, the great white shark shows remarkable characteristics in its lifestyle, diet, and reproduction.

Lifestyle of the great white shark

Great white sharks live mostly as solitary animals. Occasionally, however, they are observed in pairs or small groups, especially along coasts rich in prey. In such cases, a certain hierarchy can be recognized: larger or more experienced individuals dominate smaller ones. Their communication takes place mainly through body language. Researchers have described parallel swimming side by side, circling each other, and even strong tail slaps on the water surface. Such behaviors are likely used to signal dominance and territorial claims toward conspecifics. The great white shark is also considered curious: it often circles boats or raises its head out of the water to explore its surroundings.

The habitat of the great white shark extends across large parts of the world’s oceans. It prefers temperate coastal waters but also crosses open oceans and ventures into tropical zones. Thanks to a special network of blood vessels, this shark can maintain its body temperature up to 10 to 15 °C above the surrounding water. This physiological adaptation allows it to stay in colder waters and gives it the ability to make sudden bursts of speed.

Great white sharks are also enduring long-distance swimmers. Individual tagged specimens have covered distances of more than 10,000 kilometers and dived over 1,000 meters deep. Over the course of a day, they often stay just below the surface or at moderate depths of up to about 500 meters, but can also explore extreme depths when necessary. Overall, this flexible lifestyle contributes to the fact that the great white shark can be found in many marine regions, from the coasts of California to the waters off Australia and South Africa.

Diet of the great white shark

As a carnivore, the great white shark adapts its diet to the available prey and its own body size. Young sharks mainly hunt smaller fish, squid, and crabs. As they grow, they expand their prey spectrum to include larger fish such as tuna, as well as other sharks and rays. From a length of about three meters, marine mammals also become part of their diet. In regions with seal or sea lion colonies, these mammals make up a large portion of their prey, while in areas lacking such prey, large bony fish are also consumed.

Great white sharks also show themselves to be opportunists: they feed on carrion, for example the carcasses of large whales, whose fat-rich meat is extremely energy-dense. In general, adult great whites prefer fat-rich prey, as it allows them to meet their energy needs most efficiently. Humans, however, are not part of their prey spectrum – the human body has a low fat content in water and does not fit their hunting pattern. The very rare attacks on humans are, in most cases, likely due to mistaken identity (such as with seals or sea turtles) or territorial defense.

When hunting, the great white shark relies on surprise and powerful attacks. It often shoots up from the depths and strikes prey from below at high speed. Especially during seal hunts off South Africa, adults have been observed attacking with such force that they completely leap out of the water. When a great white catches a large prey animal, it usually bites once and then releases it to avoid injury from counterattacks. The severely wounded victim weakens within a short time. The shark waits and then returns to feed. Smaller animals, on the other hand, are often swallowed whole right away.

The serrated, triangular teeth and the enormous jaw strength allow the great white shark to overpower even defensive prey. Estimates suggest that its bite force ranks among the strongest in the entire animal kingdom. After a large meal, the shark can go for weeks without further food. A single large seal, for example, provides enough calories to meet its energy needs for up to a month.

Reproduction of the great white shark

The reproductive biology of the great white shark is extraordinary in many respects and still not fully understood. What is certain is that this species reaches sexual maturity very late: males at around 26 years of age, females only at about 33 years. Little is known about their mating behavior in the wild. Scars on the pectoral fins of some females suggest that males hold their partners during mating with a bite, as is also known from other shark species.

Great white sharks are ovoviviparous: the fertilized eggs remain in the mother’s womb, and the embryos hatch from the egg case before birth. The young are therefore born fully developed and alive. During embryonic development, the unborn sharks first feed on the yolk of their eggs and later on so-called “nurse eggs” – unfertilized eggs that the mother produces in the uterus to nourish them. The exact gestation period is unknown, but estimates suggest at least twelve months. Per litter, a female usually gives birth to only a few offspring, typically between two and ten pups.

The newborn young (juvenile sharks) already measure about 120 to 150 centimeters in length and weigh 25 to 30 kilograms, making them remarkably large. Nevertheless, they lose some weight in the first weeks as they learn to hunt on their own. Young great white sharks prefer to stay in coastal nursery areas, where they prey on smaller fish and squid and are relatively safe from large predators. As they grow, they gradually shift their range into deeper waters and tackle increasingly larger prey until they eventually reach the hunting spectrum of adult sharks.

The great white shark is among the longest-living fish species. Individual findings suggest that some specimens can live for more than 70 years. The combination of long lifespan, late onset of reproduction, and low number of offspring means that populations grow only very slowly. Over the course of its long life, a female produces only a few litters, which is extremely unusual for fish. With its unique characteristics in lifestyle, diet, and reproduction, the great white shark embodies a singular apex predator of the seas. At the same time, it symbolizes the enduring fascination that the oceans and their great hunters inspire.

The great white shark and humans

The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is one of the most famous predators in the world. Hardly any other species stirs as many emotions, stories, and headlines. It is often portrayed as a ruthless hunter, but the picture is more complex. Modern research shows that its encounters with humans usually unfold differently than popular movies suggest.

Myths and reality

In public perception, the great white shark is often seen as an aggressive danger. In reality, attacks are rare. Scientists suspect that many incidents are due to mistaken identity: from the shark’s perspective, surfers or swimmers can resemble seals, its preferred prey. In most documented cases, the shark lets go after an initial bite, as humans do not match its natural food.

Why do attacks happen?

The reasons for interactions with humans are varied. Some researchers view attacks as an exploratory reaction. Great white sharks are curious and use their teeth to investigate unfamiliar objects. Other incidents are linked to typical hunting behavior in regions where seal colonies live. Nevertheless, the risk for swimmers or divers remains extremely low.

Statistics and research findings

Worldwide, only a few dozen encounters between humans and great white sharks are reported each year. Only a fraction of these end fatally. By comparison, many other everyday risks are far more dangerous. Research also shows that most interactions are not marked by aggressive behavior but by caution and curiosity.

Geographic focus

Most incidents occur in regions with a high presence of great white sharks, such as South Africa, Australia, or California. There, the animals’ habitats overlap with popular beaches and surf areas. What is crucial is that such encounters remain rare, even though millions of people visit the coasts every year.

Tourism and encounters under controlled conditions

Great white sharks are not only feared but also a magnet for adventurers. In some countries, shark dives in secure cages are offered. These experiences make it possible to get close to the animals and observe them in their natural behavior. At the same time, they contribute to education and raise awareness for the protection of this threatened species.

Protection status and measures

The great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) is one of the best-known shark species and at the same time highly endangered. Overfishing, bycatch, and the demand for fins have significantly reduced populations worldwide. For this reason, it is considered strictly protected in many regions. The IUCN Red List classifies the great white shark as vulnerable.

International regulations

At the global level, the great white shark is protected under the Washington Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES). International trade in shark parts is strictly regulated. In addition, many countries prohibit targeted fishing, trophy hunting, and the trade in jaws or teeth. The great white shark is also explicitly included in many marine protected areas.

Regional protection measures

The protection of the great white shark is regulated differently across regions. Some countries have implemented comprehensive protection programs, while others still have ground to make up.

Australia

Australia is considered one of the hotspots for great white sharks. Here, the species has been under full protection since the 1990s. Research, monitoring, and the establishment of marine protected areas are among the most important measures. Nevertheless, incidents involving swimmers or surfers regularly spark debates about safety nets and targeted killings, which remain highly controversial.

South Africa

South Africa has recognized the importance of the great white shark both for the ecosystem and for tourism. Since the 1990s, fishing has been prohibited. At the same time, the country is known for cage diving, which is scientifically monitored and subject to strict regulations. Protected areas such as Table Mountain National Park include important hunting and migration grounds for the sharks.

USA (California)

In the United States, great white sharks are legally protected in several states. California granted the species protection as early as the 1990s. Fishing and trade are prohibited, and there are also large-scale research projects on the migration and behavior of these animals.

Mexico

Mexico has also introduced protection measures for the great white shark. Since the early 2000s, fishing and trade have been prohibited. Important habitats, particularly around Isla Guadalupe, are under special protection and are closely monitored. The island has also become a renowned destination for cage diving, which contributes to both research and ecotourism.

Europe and the Mediterranean

In the Mediterranean, the great white shark has sharply declined. Sightings are now extremely rare. Nevertheless, it is also protected here. The European Union prohibits targeted fishing and trade, but bycatch remains a problem. Experts call for stricter controls and more protected areas to safeguard the remaining populations in the long term.

New Zealand

New Zealand has fully protected the great white shark since 2007. The country prohibits both fishing and the possession of shark parts. Important habitats exist especially around the Chatham Islands and Stewart Island, which are regularly monitored by researchers.

Challenges in protection

Despite international efforts, numerous challenges remain. Bycatch in commercial fisheries, illegal hunting, and climate change continue to threaten the species. In addition, protective measures often conflict with the safety interests of coastal regions where shark attacks make headlines.