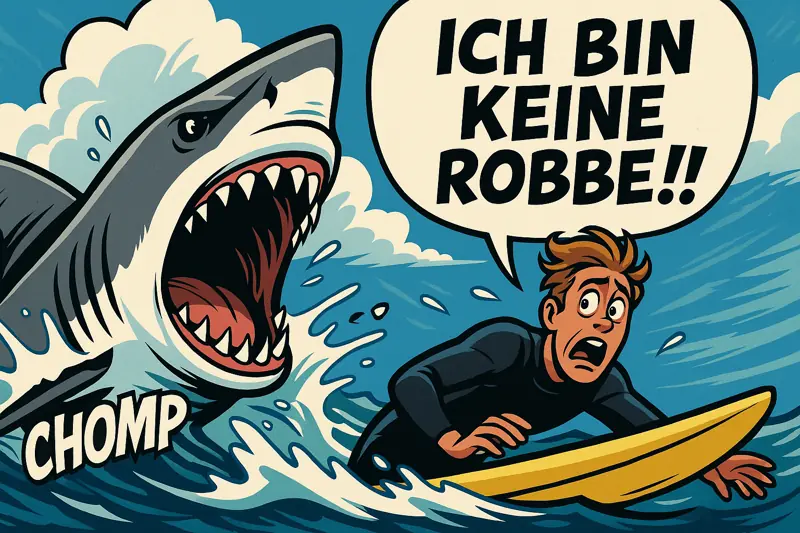

People often say: sharks mistake us for seals. This one-sentence explanation is too simplistic. Some studies support the idea that the silhouettes and movement patterns of surfers and seals can appear similar to young great white sharks. Other experts disagree, stressing that many bites are more likely curious explorations and that sharks use multiple senses, not just rough outlines. Realistically: depending on the situation, confusion can occur, but it is by no means the only or most important explanation.

Where does the idea of confusion come from?

From an underwater, backlit perspective, shapes blend more easily. Experiments with silhouettes and videos suggest that, in particular, juvenile great white sharks may find it difficult to distinguish surfers and small seals at certain angles. This makes confusion plausible, but not a general rule.

The opposing view: exploratory bite instead of confusion

Other researchers criticize the mistaken-identity narrative as too human-centered. Many incidents are better explained as exploration: sharks often test the unknown with a brief bite and then disengage. This argues against the idea that people are regularly mistaken for intended prey.

Brief note: warning signs before bites

Many shark species send clear warning or defensive signals before escalating, for example slightly lifting the head, lowering the pectoral fins, arching the back, stiff S-curves, or short zigzag approaches. These are context-dependent attempts at de-escalation; in ambush-style hunting attacks, such warnings are often absent.

What do observations in the ocean show?

In coastal areas with seal colonies, juvenile great white sharks often swim past people without biting. This suggests that we are generally not target prey and that context, such as visibility, prey presence, and behavior, makes the difference.

What does this mean for divers and surfers?

Context matters: visibility conditions, nearby prey, currents, and your own behavior. Staying calm, avoiding rushing, remaining in groups, avoiding dawn and dusk, steering clear of prey schools, and not carrying spearfishing catch on your body are practical basic rules that further reduce the risk.

Conclusion

The statement “sharks mistake us for seals” is too simplistic. Confusion is possible in certain situations, but many bites are more a matter of exploration than hunting. Most encounters are peaceful, and those who recognize warning signs and choose smart behavior further reduce the already low risk.