Body Structure, Characteristics & Anatomy

The blue shark (scientifically Prionace glauca) is one of the most well-known and elegant shark species in the world's oceans. With its streamlined body and characteristic bluish coloration, it is not only visually striking but also a fascinating example of perfect adaptation to life in the open sea.

General characteristics of the Blue Shark

Appearance and Coloration

The blue shark owes its name to its intense, metallic shimmering coloration: the upper side is bright blue to steel blue, while the underside is light gray to almost white. This color play serves as camouflage in the open ocean —blending with the darker depths from above and with the bright light of the water surface from below.

Body Structure

Blue sharks are elongated and extremely slender, which gives them high agility and speed in the water. They typically reach a length of 2 to 3 meters, with females tending to grow larger than males. Their body shape is perfectly adapted to a pelagic lifestyle – that is, life in the open ocean, far from the seafloor.

Anatomical Features

Head and Snout

The head of the blue shark is elongated and pointedwith large, round eyes that are excellently adapted to the light conditions in deeper water layers. The snout is relatively long, which benefits it when hunting fast prey such as squid, mackerel, or sardines.

Teeth

A typical feature of the blue shark is its tooth pattern with sharp, triangular teeththat are slightly curved backward. This shape allows it to effectively grasp and hold onto prey. The teeth are arranged in multiple rows and are quickly replaced when lost – a typical trait of all sharks.

Upper jaw of the blue shark

Dentition of the blue shark, Luca Oddone, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Lower jaw of the blue shark

Fins

The blue shark has:

- A distinctive long, sickle-shaped pectoral fin

- A relatively small first dorsal fin, positioned further back than in many other shark species

- A second, smaller dorsal fin near the tail

- An asymmetrical tail fin (heterocercal), with the upper lobe significantly longer – a typical feature of fast swimmers

Differences between males and females

Size and weight

There is a noticeable difference between the sexes in terms of body size: female blue sharks are on average larger and heavier than their male counterparts. While males rarely grow beyond 2.5 metres, females often reach lengths of over 3 metres.

Skin structure

Females have thicker skin than males - an evolutionary trait that protects them from injury during mating. Male blue sharks bite into the flanks of females during the act of mating, which can lead to deep bite wounds. The thicker skin therefore serves as a natural protective mechanism.

Genital organs

Another distinguishing feature are the so-called claspers - paired mating organs that are located on the inside of the ventral fins in males. Females do not have these structures. This distinction makes it possible to clearly determine the sex of the fish when it is sighted or caught. Females have paired uteri; males have Clasping for internal fertilisation.

Adaptation to the habitat

Blue sharks are highly specialised hunters that are characterised by a variety of anatomical adaptations. Their slender body reduces water resistance, their well-developed musculature allows them to sprint quickly, and their senses - especially smell and lateral line organs - enable them to detect prey over long distances.)

Distribution & Habitat

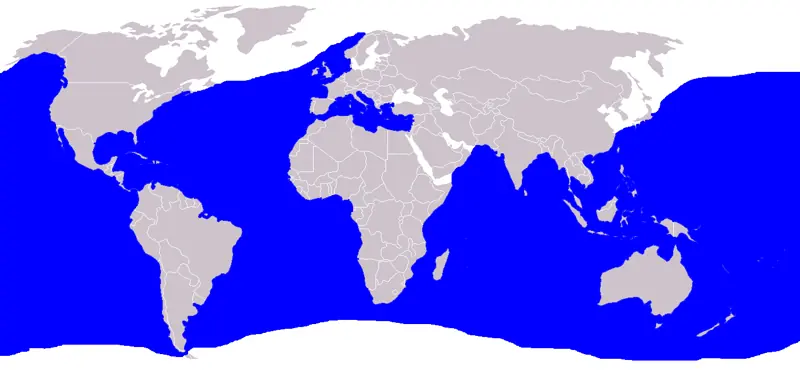

The blue shark (Prionace glauca) is a pelagic large shark with a circumglobal distribution in temperate and tropical marine regions. It occurs from about 70° north latitude to 55° south latitude and inhabits all major oceans. Known occurrences include the North and Southatlantic (Newfoundland to Argentina; Norway to South Africa including Mediterranean Sea), and in the Indo-Pacific (East Africa to Japan and Australia; in the Pacific to Chile). The blue shark avoids polar regions.

Worldwide distribution

An inhabitant of temperate and tropical waters

The blue shark can be found in almost all of the world's oceans. It prefers temperate to tropical waters and only avoids the polar zones. It is particularly common in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Ocean occurs. It is also a regular, albeit now rare, guest in the Mediterranean.

Occurrence in the Atlantic

In the Atlantic Ocean, its range extends from Norway to South Africa and from Canada as far as Argentina. The North Atlantic in particular plays an important role, as the blue shark is of interest here both for scientific studies and for fishing.

Pacific and Indian Oceans

In the Pacific, the blue shark is regularly spotted off the coast of Japan, Australia, California and Chile. In the Indian Ocean, its habitat also extends over long distances, for example off the east coast of Africa and around the islands in the Indian Ocean.

Habitat of the blue shark

Deep-sea dwellers with a large radius of action

The blue shark prefers the open sea, the so-called pelagic zone. It usually moves at depths of 100 to 350 metres, but occasionally dives to depths of up to 1000 metres. It is considered one of the most active deep-sea sharks and travels long distances, sometimes over thousands of kilometres.

Temperature and environment

They prefer water temperatures between 12 and 25 degrees Celsius. In these areas, the blue shark finds ideal conditions for foraging and reproduction. Cold regions, on the other hand, are avoided, which explains its absence in Arctic waters.

Migration behaviour

The blue shark is a pronounced migrant. Every year, it makes seasonal migrations, for example to seek out cooler or warmer waters or to reach breeding grounds. This mobility makes it particularly vulnerable to international fisheries policy and environmental changes.

Ecological importance and protection status

As a predatory fish at the top of the food chain, the blue shark fulfils an important role in the marine ecosystem. It keeps the populations of smaller fish and cephalopods in balance. At the same time, it is threatened by overfishing and bycatch, which has already led to drastic population declines in some regions.

Reproduction

Like many requiem sharks, the blue shark gives birth to live young (viviparous) and nourishes its embryos in the womb via a yolk sac placenta. The reproduction rate of this pelagic large shark is comparatively high: several dozen young are often born in individual litters. Reproduction is cyclical; after reaching sexual maturity (males from approx. 4-5 years, females from approx. 5-7 years), a female can usually give birth annually or in some cases only every two years.

Mating behaviour

The mating of the blue shark is characterised by a strong clasping. Males insert their clasping organ (clasper) into the female and often hold her to their body with their teeth. The male typically bites into the female's dorsal or pectoral fins to gain support. As a result, adult females have significantly thicker skin in the area of these fins than males - a protective mechanism against injuries caused by bite marks from previous mating. Mating itself has only rarely been observed directly, but the thick, scarred areas of skin on females and the young still born alive confirm the mating process described.

Gestation period and duration of pregnancy

After fertilisation, the embryos develop in the womb for around nine to twelve months. The gestation period is therefore in the middle of the year, which means that birth is typically delayed until spring or summer. During this time, the young sharks feed on a yolk sac placenta, which supplies them with nutrients. After around a year of gestation, the female will give birth to fully developed young.

Litter size and young animals

The litter size of blue sharks is very variable. Litters of several dozen young are common: On average, a female blue shark gives birth to around 15 to 30 young, but in extreme cases over a hundred offspring have been documented in one litter. Smaller females give birth to correspondingly fewer young, while larger and more experienced females can carry significantly more embryos. At birth, the young are already relatively large: they measure around 35 to 50 centimetres and resemble miniature adult sharks. This means that they are largely independent right from the start and can hunt and react immediately.

Birthplaces and nurseries

Blue sharks do not give birth to their young in shallow coastal waters, but in the open high seas. Their so-called nurseries (birthing and breeding areas) are often located in nutrient-rich transition zones of the ocean. Studies show that juvenile blue sharks spend their first years of life in larger marine areas, far away from coasts. For example, a large "nursery" area has been identified in the North Atlantic near the Azores, where young sharks remain for around two years. In these offshore nurseries, the young animals can initially develop undisturbed. In fact, both male and female blue sharks regularly return to such areas to mate and give birth to young. Waters off western Europe and north-west Africa are also considered important birthing regions for blue sharks. In German waters, however, births are not usually observed, as the animals are usually only on the move here.

Food & Enemies

The blue shark is an active predator with a varied diet that can vary depending on location. In general, its main diet consists of small bony fish such as herring, sardines and mackerel as well as molluscs such as squid, cuttlefish and pelagic octopus.

Prey of the blue shark

Studies show that blue sharks favour different prey in different regions. For example, in the waters off Brazil found that blue sharks in the southern area include baleen whales, bony fish such as Ruvettus pretiosus and Arioma bondi and various molluscs such as Histioteuthis spp., Cranchiidae and Ocythoe tuberculata eat. In the north-eastern part of Brazil, their diet includes bony fish such as Alepisaurus ferox and Gempylus serpens and molluscs such as Histioteuthis spp. and Tremoctopus violaceus. In addition, birds, including Puffinus gravisfound in the stomachs of blue sharks from both regions.

Blue sharks are also known to eat larger prey, including other sharks. Sharks and carrion from mammals such as whale and dolphin meat and fat. In some cases, they have been observed eating seabirds and even cod from trawl nets. They feed around the clock, with increased activity at night.

Blue sharks often work together to herd schools of fish, which makes it easier for them to catch their prey. Their triangular teeth and high swimming speed are ideal for catching elusive prey such as squid and fish. This cooperative hunting strategy emphasises their social intelligence and adaptability.

| Region | Main prey animals | Additional prey |

|---|---|---|

| Southern Brazil | Baleen whales, Ruvettus pretiosus, Arioma bondi, Histioteuthis spp., Cranchiidae, Ocythoe tuberculata | Seabirds (Puffinus gravis), crustaceans |

| Northeastern Brazil | Alepisaurus ferox, Gempylus serpens, Histioteuthis spp, Tremoctopus violaceus | Seabirds (Puffinus gravis) |

Predators and threats

Despite their role as apex predators in many ecosystems, blue sharks themselves have natural predators. Larger sharks such as the Great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) and the Shortfin Mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) hunt young and smaller blue sharks.

Killer whales (Orcinus orca) are known to hunt blue sharks. In addition, some marine mammals such as California sea lions (Zalophus californianus), northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) and South African fur seals (Arctocephalus pusillus) watching them eat blue sharks.

Blue sharks can also harbour various parasites, including tapeworms such as Pelichnibothrium speciosumwhich they obtain by feeding on intermediate hosts such as moonfish (Lampris guttatus) and longnose grenadiers (Alepisaurus ferox). Research suggests that predators often attack blue sharks from behind, targeting the caudal fin, which makes it more difficult for them to escape.

| Predator | Description |

|---|---|

| Great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias) | Larger shark hunting smaller blue sharks |

| Tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) | Opportunistic predator attacking juvenile blue sharks |

| Shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus) | Fast shark that hunts blue sharks |

| Killer whale (Orcinus orca) | Known for attacks on blue sharks |

| Marine mammals | California sea lions, northern elephant seals, Cape fur seals |

| Parasites | Tapeworms like Pelichnibothrium speciosum |

Interaction with people

Encounters of the blue shark with humans

Under normal conditions, human encounters with blue sharks usually take place on the high seas. Blue sharks mainly live in pelagic waters and are rarely found in coastal habitats. If divers, snorkellers or anglers encounter a blue shark, it is usually harmless: the shark is considered curious and not very aggressive and usually approaches slowly out of interest. In general, a blue shark quickly recognises that humans are not typical prey, so incidents rarely escalate.

Diving and snorkelling

When diving in the open sea - for example off the Azores - blue sharks can circle diving teams. After initially holding back, the animals often approach cautiously and inspect the divers with their fine sensory organs. During a typical dive, five to fifteen blue sharks can often be seen moving slowly between the divers and the boat. Spearfishermen can also encounter blue sharks: in clear diving areas, food fish - or the catch brought along while diving - attract the sharks. Overall, human-shark interactions here are usually calm, as blue sharks hardly perceive humans as prey. There is a small residual risk of a shark tugging on or testing prey out of curiosity.

When angling and deep-sea fishing

Blue sharks are also occasionally encountered when fishing on the high seas. For sport and recreational anglers, the blue shark is a sought-after game fish, as it pulls energetically on the fishing rod or longline. In commercial fishing, however, blue sharks are often regarded as an annoying by-catch: They snatch prey from hooks or become entangled in nets and longlines themselves. In both cases, the sharks mainly approach where fishing lures or caught fish are floating in the water. Worldwide, the annual catch of blue sharks totals around 20 million animals - mainly as unintentional by-catches in longline and trawl fisheries.

Blue shark attacks on humans

Despite the impressive size of the blue shark, the risk of an attack on humans is extremely low. According to data from the International Shark Attack File (ISAF), only 13 unprovoked blue shark bites have been documented worldwide, some of which occurred in the context of aircraft or ship accidents. Vulnerable situations have mainly occurred for shipwrecked people and open divers in the vastness of the ocean. Blue sharks hardly ever occur near the coast, which is why attacks on bathers or coastal divers are practically unknown and rather exaggerated from an ecological point of view are. Overall, the danger when diving or swimming remains minimal; at most, blue sharks may bite an object or inedible prey out of curiosity, which usually does not result in serious injury to humans.

Importance of the blue shark for fisheries

Catches and bycatch

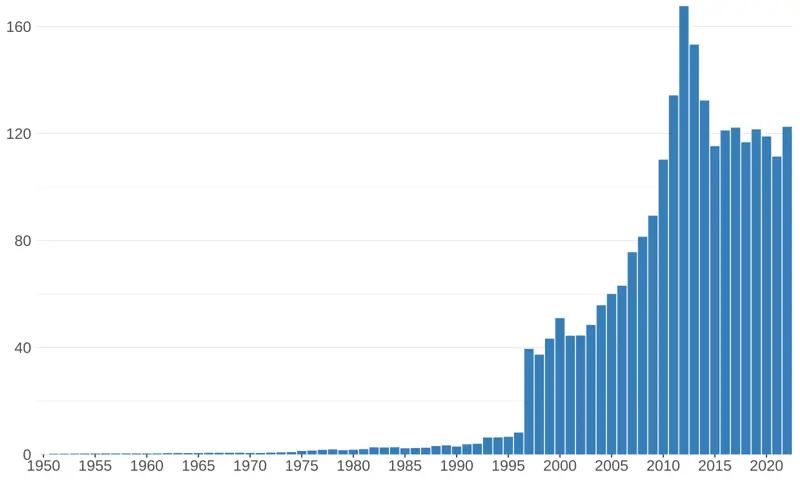

The blue shark is the most heavily fished shark in the world. It is estimated that around 20 million blue sharks are caught every year. Since the 1990s, global catches have risen rapidly, reaching a peak of around 137,973 tonnes in 2013. Since then, catches have fallen again significantly, which is seen as an indication of the species' declining abundance. In the Atlantic in particular, blue sharks account for the majority of all commercial shark catches at 85-90 %. These enormous catch figures are largely due to deep-sea fishing: blue sharks become entangled as by-catch in longlines and nets by nibbling on bait fish or attacking other fish they have caught. It is estimated that between 10 and 20 million blue sharks die in fishing gear in this way every year.

Utilisation and marketing

Due to its high uric acid content, the meat of the blue shark has a distinct flavour of its own and is rarely marketed directly worldwide. It is only used as food in some regions - for example in parts of South-East Asia and Japan. Shark fins, on the other hand, are in high demand: they are mainly sold on the world market for the preparation of shark fin soup. The skin of the blue shark is also utilised, for example as leather. In many countries, whole-body processed blue shark products reach the market, and in the EU with its finning bans, only sharks from which no fins have been removed may be traded. Despite this, Asian markets in particular have long benefited from the high blue shark catch. Due to the persistently high catches, the blue shark is now on the Red List as potentially endangered

Threat & protection status

The blue shark is one of the most widespread shark species in the world's oceans, but its population is increasingly endangered. Despite its widespread distribution, intense fishing pressure, bycatch and the demand for shark fins are causing serious problems for the pelagic predator.

Main causes of the hazard

The threat to the blue shark comes mainly from human exploitation. The species is targeted on a large scale or killed as bycatch in longline and trawl fisheries. Finning, in which the shark's fins are removed before the rest of the body is thrown back into the sea, is particularly problematic. As blue sharks are relatively common in many regions of the world's oceans, they are one of the most heavily exploited shark species. The high catch rate also persists because their meat, fins and skin can be utilised commercially.

Development of inventories

Although exact global population figures are difficult to determine, scientific studies indicate a long-term decline in blue shark populations. A significant decline can be observed in the Atlantic and Mediterranean in particular. In some regions, a Decline of up to 70 per cent within a few decades. The main reasons for this are the low reproduction rate and the high rate of removal by fishing. The young animals take several years to reach sexual maturity, which significantly slows down the rebuilding of the population.

Protective measures at international level

Some international agreements and initiatives are now attempting to better protect the blue shark. For example, it was included in the Convention on Migratory Species (CMS) and is subject to catch restrictions in several fishing zones. The EU has also taken measures, including catch quotas and a ban on finning. Nevertheless, the existing regulations are often inadequate or are not effectively enforced. Many blue sharks continue to die as unwanted bycatch or enter the trade via unofficial markets. The high economic value of the fins makes it difficult to consistently implement protective measures.

IUCN assessment and current conservation status

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) lists the blue shark as "Near Threatened" on its Red List. This classification means that although the species is not yet directly threatened with extinction, it could move into a higher threat category in the near future if the trend continues. The blue shark already fulfils several criteria that indicate an unfavourable conservation status. The classification by the IUCN is based on comprehensive data surveys on catch numbers, reproduction rate, distribution area and population structure.